It would be an understatement that 2008 was a year of surprises. In the early part of the year, even world-class economist John Rutledge noted that the businesses could take refuge in the fact that the sub-prime mortgage crisis had not impacted business lending. But as that thin wall of protection evaporated, the impact on digital cinema growth was all too apparent. The long anticipated rollout of digital cinema, which so heavily rests on the plans of major US exhibitors, failed to materialize.

To facilitate the rollout of digital cinema, major US exhibition chains AMC, Cinemark, and Regal Entertainment banded together in early 2007 to form Digital Cinema Implementation Partners (DCIP). DCIP’s primary scope is to raise money and individually negotiate subsidizing payments from the major film studios through a mechanism called virtual print fees, or VPFs. (More can be learned about VFP financing at http://mkpe.com/faqs/). Early in 2008, DCIP indicated that it had secured a $1B line of credit through JP Morgan. All that was needed was the signing of VPF agreements with the major studios.

In September, immediately after the Lehman Bros bankruptcy, word came that the private investment community was being pitched by DCIP, indicative that the line of credit with JP Morgan was no longer available. This gave a hollow ring to DCIP’s announcement on Oct 1 that it had signed VFP agreements with five studios. (The five included Lionsgate, which is not counted in this report as a major studio.) To cover itself, JP Morgan and Blackstone Group issued a separate statement with Reuters, also on Oct 1, carefully stating that they ”look to raise over $1B.” Behind the scenes, it was apparent that the rules for lending had changed: DCIP would now have to jump over a much higher hurdle to raise the $1B necessary for its rollout. Altogether this was bad news for the manufacturing community. The long awaited purchase orders would not be forthcoming.

Let’s look at the figures.

While the number of digital cinema installations grew in 2008, the rate of growth was significantly less than in prior years. The chart above shows the number of installations over time (yellow curve) and the relative rate of growth (green curve).

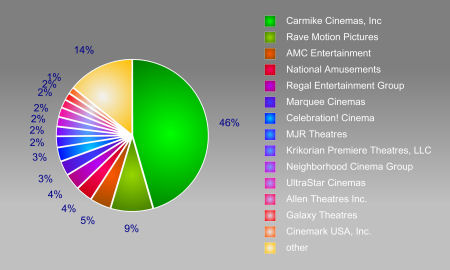

On the plus side, the number of circuits that have installed digital systems has grown significantly beyond that of Carmike Cinemas and Rave. But Carmike remains, by leaps and bounds, the largest operator of digital theatres in the world. The pie chart below shows the number of installations by circuit in the US. (Data from DCinemaToday.com, estimated to be accurate for mid-2008.)

Digital cinema growth remains plagued by a few basic factors:

- The question of ROI for the exhibitor. 3-D ticket premiums have proven to be a positive growth factor for digital projection, and single-screen revenues from alternative content have improved. But the ROI for 100% conversion is still hindered by the 200-300% increase in cost of ownership.

- Financial worthiness of the equipment. Equipment has yet to be tested for DCI Compliance. (DCI stands for Digital Cinema Initiatives, a joint venture of the 6 major film studios. DCI publishes its technical specification and Compliance Test Plan at http://dcimovies.com ) With DCI compliance written into VPF financing deals, and lending policies now tightened up, banks are shy to accept anything less as collateral.

Further complications are surfacing. Studios are facing reductions in advertising, production, and DVD sales, all of which are causing cutbacks in the industry. Existing VFP agreements are likely to survive as they are designed to be cost neutral to the studio. But if Kodak should continue to drop film prices, studios may be forced to reassess. There are other complications unique to DCIP which are discussed later in this report.

The industry has little control over most of these events, but some can be fixed. Texas Instruments plays a command role in digital cinema as the core provider of DLP Cinema™ projection technology, yet has failed to take the right steps in moving digital cinema forward. The company has known since 2004 that it would have to upgrade the input to its projector to meet DCI’s (then proposed) security requirements. But even after the spec was adopted in 2005, TI chose to defend its design as good enough – an argument which it lost with finality in 2008. This snafu will lead to the mandatory installation by TI’s OEMs of the “Gore board,” a secure input replacement board for all 2K DLP Cinema projectors. It’s a compromise solution for meeting studio security requirements that will not be cheap to retrofit in existing installations.

TI’s failure to upgrade its design for DCI security and SMPTE subtitles and captions will delay the DCI compliance rating for projectors until 2010. Given the difficulty in financing non-compliant equipment, and that projectors are the highest cost item in a digital cinema system, this is a serious misstep and has hurt the ability of its DLP Cinema OEMs (Barco, Christie, NEC) to sell products.

TI missed in another important way, too. In its non-cinema line of DLP products, Delta Electronics, a major OEM-only manufacturer of DLP projectors, claims the ability to build 5-6K lumen DCI compliant projectors in the $25K-$30K price range. It can bring down the cost by sharing the core product platform with higher volume products. Delta is probably not alone in having this capability. Such projectors would meet the price and light level needs of at least 50% of screens around the world, and at least 40% of screens in the US. But TI is reticent to change its complex licensing arrangement with its three OEMs to allow companies such as Delta the right to produce DLP Cinema projectors. While some exhibitors get quotes today in the $35K price range, assuming a large quantity sell, the majority of exhibitors are quoted projector prices well above $50K. Today’s high prices strongly hinder market adoption. TI’s licensing policy will have to change if this market is to open up.

On the technology side, perhaps the largest but most understated issue is the inability of system suppliers to provide closed captions and narrative audio. In the US, the magnitude of this issue grows as the Federal Department of Justice, and several State Attorney Generals, ponder the requirement of accessibility in theatres. Film is inherently crippled when it comes to providing such features, with only one viable closed caption system available with film today. (While there are multiple contenders that wish to offer closed captions for film, only one, WGBH, has negotiated a distribution channel.) The same is true for narrative audio for film. Digital cinema has the ability to open up the distribution methods for a/v access, and will bring competition, and hopefully lower prices, to the closed caption market. Legal entities have been told as much. But these technologies are not yet ready for digital systems, and the installation of digital cinema systems without the necessary access features could cause litigation problems.

Milestones

2008 witnessed its share of milestones. DCI released v1.2 of its Digital Cinema System Specification, followed by several releases of “errata.” DCI selected and authorized three test centers around the world for testing products to its specification. NATO released v2.1 of its Digital Cinema System Requirements. Several virtual print fee deals were announced by DCIP, GDC, XDC, Arts Alliance, and Cinedigm (formerly AccessIT). Dave Schnuelle of Dolby took over the leadership of the SMPTE digital cinema standards effort, which coincidently was imposed a name change from DC28 to 21DC.

2008 was also witness to a few losses. Digeserv, aka Digital Entertainment Services LLC, was competing for services with Cinema Buying Group. (See the CBG section later in this report.) Digeserv failed to successfully negotiate VPF agreements with studios, and thus lost its bid to CBG. Nothing has been heard from the company since, and it’s assumed that it shut its doors.

QuVis, the first digital cinema server company, also closed its doors in 2008. QuVis had more opportunity than most to become a winner in the digital cinema server business. It was a leader in wavelet applications, which is the core technology in JPEG 2000 compression. However, it persisted far too long with its proprietary version of wavelet compression, losing confidence with potential customers, and opening the door for competition. QuVis was in the winning bid for UK Film Council’s 240-screen Digital Cinema Network, but early installed units were eventually replaced by Doremi servers after the company delayed the incorporation of studio-required watermarking.

The biggest news of the year, unfortunately, was negative: the credit freeze experienced in business lending. The majority of digital cinema equipment purchases are financed by virtual print fees (VPFs), a complex arrangement whereby studios subsidize the purchase. The complexity, lack of familiarity, and lack of compliant equipment places the financial backing for this mechanism in a perceptibly higher risk category. As a result, bank financing has become increasingly difficult. All monies raised in 2008 for VPF financing were from private sources.

The Future

Until equipment prices drop significantly, it’s unlikely that digital cinema will experience a speedy adoption rate. But it’s inevitable that the technology will eventually permeate the market. The question, then, for manufacturers and service providers, is how to pace one’s business for this scenario? A slow market can only support a small number of players in any one region. Competition will only get tougher. Coupled with financially tight times for both exhibitors and studios, competitors will likely become more cut-throat in their manner of doing business until there is a reduction in the number of players.

On the brighter side, there remain opportunities to be explored. The satellite delivery problem in the US, for example, is a train wreck waiting to happen. This is an area that is experiencing multiple investments in duplicative hardware, and the marriage of high-caliber services to proprietary Theatre Management Systems (TMS). Competitors in this space tend to play a game of all-or-nothing, but customers do not want monopolies. They want competition. There are strategies for taking advantage of this situation, but they require collaboration, and no one as yet has shown the wherewithal to take such steps.

Another problem area that spells out opportunity is the delivery of KDMs to installations where there is no TMS. It’s not a highly visible problem as yet, as most installations have a TMS. But given the slow nature of the rollout, the large number of sites in the world that house only a few screens, and the high likelihood of only one or two installations per site for 3-D in the foreseeable future, there is an opportunity for those who provide cheaper, scalable solutions for receiving KDMs other than a TMS.

In my end-of-year report for 2007, against all sensibilities, I made a number of predictions for 2008. Some came true, some did not. I’ll review these in the course of this report. (Humorously, my prediction that industry veteran Jerry Pierce would take a job was wrong.)

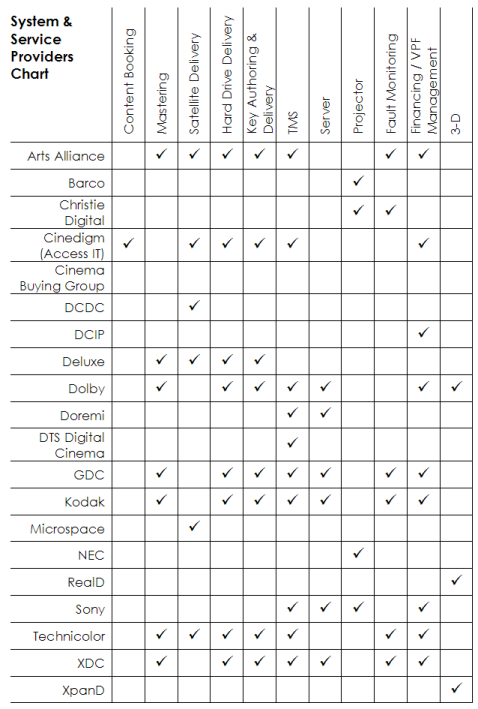

The remainder of this report provides a review of the activity and challenges for the major technology and services providers in digital cinema.