With the eventual introduction of the TI Series 2 projector comes a security issue that must be dealt with. TI diligently followed the DCI specification in its Series 2 design, choosing a security topology that involves two security devices, or SPBs (Secure Processing Blocks), within the body of the projector. Technically, this leaves two certificates to track and include in the security key’s trusted device list. (In acronym-land, the TDL in the KDM.) The SMPTE standard for retrieving the certificate in the projector, called ASM (for Auditorium Security Message), can only pull one certificate. Herein lies a very significant problem.

If the SMPTE standard is changed to pull two certificates from the projector, then 10,000 servers now in the field will be unable to drive the forthcoming Series 2 projector. The existing servers can’t be changed without undergoing considerable expense, as, for most designs, the entire FIPS-certified media block must be changed out with a new media block that implements the revised command. In addition, the company that manufactures the new media block has to undergo a new FIPS certification for the revised design. All of this takes time and money.

If the time and money aren’t spent, a likely scenario, then the industry will end up with two classes of 2K servers in the field: those that can drive the Series 2 projector, and those that can’t. Such differentiation can dramatically devalue the server that can’t.

The question has been raised by several people as to whether or not security is really compromised by not having the ability to disable one of the security managers in the Series 2 projector.

The argument goes like this:

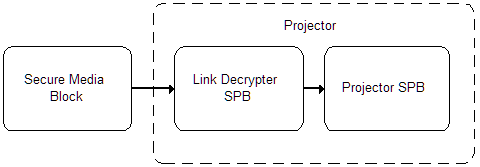

In the drawing above, the secure media block is inside a server, and the projector in question has two secure processing blocks: one for link decryption, and another for the core projector. Industry requirements dictate that the link decrypter SPB must be installed by a qualified and trusted technician such that the link decrypter becomes “married” to the projector SPB.

The crux of security in this case is for the media block to know, by means of the trusted device list (TDL) in the security key (KDM), that it is connected to a valid projector. The link decrypter is already trusted, since it is tamper responsive, and installed by a trusted technician who married it to the projector. The purpose of the TDL is to manage isolated problems. I.e., if a projector is known to be out-of-service or to have been modified in an unacceptable manner, then the content owner may refuse to allow the KDM to play its content on this projector.

The link decrypter is FIPS certified, which means it has undergone a rigorous examination for managing secure transactions and cannot be tampered with. Since the link decrypter receives its encrypted data from the media block, and transmits encrypted data to the projector SPB, a hack of the link decrypter would not be an isolated problem. If the link decryptor was hackable, then an entire series of product would be at risk. From a security view, the link decrypter cannot be effectively managed by a trusted device list, as a problem in such devices will not be isolated. The projector, however, is not FIPS certified, and can be hacked in an isolated manner. A security problem with a particular projector can be effectively managed by a TDL.

This simple analysis indicates that there is no advantage to blacklisting a particular link decrypter, and that single certificate management should be sufficient. However, content owners have yet to be convinced.

The issue goes well beyond the ASM standard. It points to the fragility of SMPTE standards and the DCI specification. One simple change can obsolete an entire generation of product. At some point, the changes must stop.