The first half of 2010 began a very different year for digital cinema. In the past, manufacturers yearned for customers. Now it is the customers that yearn for product. In a wicked twist of fate, DLP Cinema projector manufacturers have been unable to fulfill the sales they spent a decade dreaming of. One of the dangling carrots was the long awaited announcement from Digital Cinema Implementation Partner’s (DCIP) that took place in March, marking the completion of $660M in funding for 2/3 of its digital cinema rollout with AMC, Cinemark, and Regal. Another was the success of Avatar, which drove the adoption of digital cinema 3-D projectors, both before and after the movie’s engagement. Adding to the welcome news, at long last, the modem is dead. Fox is now promoting an elegant network-based approach for security key management that is getting significant attention. But a cloud appeared in January with the release of FIPS 140-2 updates by the US-based National Institute of Standards Technology (NIST), unexpectedly obsoleting the current security standards for digital cinema at the end of 2010. NIST has since made changes that delay some of the impact for digital cinema for a few more years, but only some. We explore these issues below, and provide an update on the companies engaged in this sector later in this report.

Growth

But first, the numbers.

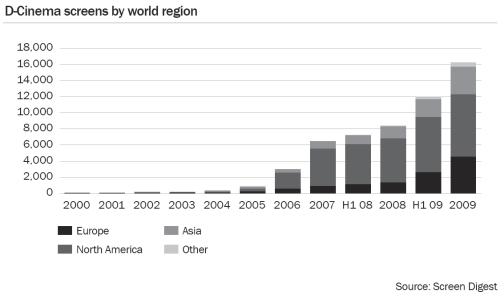

In 2009, digital cinema grew worldwide at an astounding rate. Note that the last two columns in the chart above represent the first and last half of 2009, showing uniform growth throughout the year. Note also the near tripling of screens in Europe and Asia in 2009, compared to a mere 50% in the US.

3-D

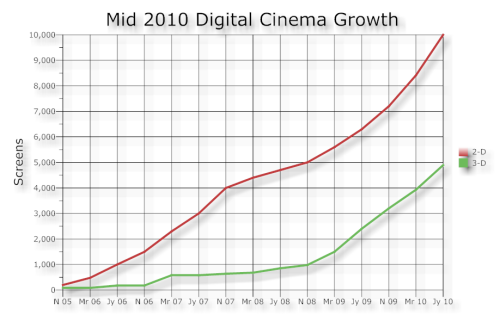

3-D remains the calling card for digital cinema, bringing the digital screen count in the US to the 10,000 screen mark in June. The format is credited for 11% of North American box office in 2009. But while Avatar popularized 3-D, the industry is in a struggle to keep the glow. Theatre owners have driven up digital 3-D ticket prices to IMAX proportions, and a flood of 3-D movies compete for too few 3-D screens. The result has been a decrease of 3-D contribution to box office per movie, a worrisome factor in light that 3-D is driving the digital transition.

The production side of 3-D is also challenged. Avatar set a high bar for quality which may be difficult to match for some time. The expert production companies behind 3-D are too few. Producers that settle for 2nd best find themselves banging on the door, mid-way through production, of the companies they turned down. They are learning that there is a big gap in know-how for making quality 3-D movies.

The result is not always impressive in the theatre. Where Avatar exceeded expectations in quality, movies such as Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender disappointed. Eager to benefit from the bump in ticket prices, and capitalizing on the opportunity to push others off the money earning screens, certain studios undertake cheap conversions from 2-D to 3-D. Studio giants no less than Jeffrey Katzenberg and Bob Iger have since jumped on the quality bandwagon, rightly sensing that any cheapening of the format will lose its appeal, and its box office premium. Interestingly, Disney also pursues 2-D to 3-D conversion, but pays for quality.

While the importance of story can never be overlooked, even story cannot make up for low quality 3-D. Quality is a necessary ingredient. In a recent panel on the subject at Cinema Expo, Universal SVP Niels Swinkels expressed the importance of quality 3-D production. Screen count is also important. To retain strength in 3-D box office, more 3-D screens are required. Fortunately, exhibition is stepping up to this need. If done well, the industry will gain. Maria Costeira, CEO of XpanD, pointed out that 3-D ticket prices were unlikely to come down, and if anything, 2-D prices would go up. (Let’s hope that the cost of popcorn will remain the same.)

The graph below doesn’t track popcorn pricing, but it does compare the total growth in digital screens with the growth of 3-D in the US. It’s clear that 3-D continues to drive growth.

Where’s My Projector?

Projector companies admirably handled the ramp up in sales preceding Avatar, with the installation count of digital screens around the world nearly doubling in 2009. What the DLP projector companies didn’t expect was that demand would continue, if not surpass, the 2009 growth rate, well into 2010. But even with that error in forecasting, which impacted orders for very long lead optical components, DLP production would be challenged. Most studios, per their digital cinema deployment agreements, required DLP manufacturers to only ship projectors having digital inputs that met DCI security requirements. None of the projectors shipped in 2009, or earlier, did so.

To achieve DCI compliance required a redesign by Texas Instruments of its core system. TI saw this as an opportunity to update the entire design and to add improvements. From the get-go, this was to be a 4K-capable design. Notably, this decision was made long before TI committed to producing a 4K imaging device. However, the development cycle took longer than the studio’s wanted, and the manufacturers were left with the short straws. Getting the new Series 2 design into production for January 2010 shipments became a difficult challenge, not always met successfully.

The combination of factors has led to the commonly heard complaint by exhibitors and deployment entities that they can no longer get projectors in a timely manner. At least one DLP projector company is quoting January delivery for orders placed in June. The impact has been felt in many places. Deployment entities are unable to meet customer demand, let alone installation targets set by studios. The 3-D footprint is restricted in its growth, affecting box office and possibly investment in future 3-D motion pictures. The great irony for studios is that they succeeded in convincing the world to adopt the DCI digital projection format, if only there was a projector one could buy.

This should have been a boon for the other projector company, Sony. Sony’s technology is the only one that does not rely on DLP light engines. But Sony’s projector production is consumed by US exhibitors Regal and AMC, who are each said to be receiving deliveries of 200 or more a month. Sony’s only announcement of new sales in the first half of 2010 was a 19 screen deal with Uptown Entertainment in Michigan.

Networks Rule

Fox has shed the modem. At the same time, it is favoring an elegantly conceived scheme for collecting the certificate information from digital cinema sites in order to correctly deliver security keys. The scheme, called FLM-x, is posted by Fox at the http://flm.foxpico.com site. (Username: isdcf, Password: isdcf.) For the uninitiated, FLM stands for Facility List Message, which is SMPTE standard 430-7, and the “x” stands for an extension of the standard, which the standard accommodates. FLM, by design, contains equipment certificate information, as well as the forensic mark identifiers associated with the equipment. It is generated at the exhibition site, and intended for security key creators. The FLM was standardized before real implementation of this message could take place, so the addition of extensions is not surprising, and should increase its usefulness as a tool for security key creation.

Most importantly, the method promoted by Fox is elegant. It is based on what is referred to as the RESTful method of web services. REST stands for Representational State Transfer, and was originated by one of the authors of the HTTP protocol, the same “http” that prefaces the address line of every web page you look at. The World Wide Web itself is a RESTful implementation. What one should take away is that nothing new has been invented, and in fact, the FLM-x method is based on methods that are quite common.

Just as it is elegant, the FLM-x method can be applied to the collection of security logs, required by virtual print fee agreements, and the networked delivery of KDMs (Key Delivery Message, SMPTE 430-1). By moving towards an open method, Fox is paving the way for it to manage its own security keys. Because the method is light weight, it can easily be adopted by any maker of a TMS or back office system in the world. It works equally well for any entity that sells security key creation services to studios, and all such entities would benefit from the wide adoption of the RESTful FLM-x method.

Fox’s movement down the path of openness brings forward much needed conversations about facility identifiers and content identifiers. In a moment of idealism, Fox once pursued a centralized identifier method utilizing bar codes. But centralized identification methods are about as popular worldwide as a universal political system. A more realistic approach accommodates the concept of different owners of identifiers. Identifying the owner of an identifier scheme, such as Rentrak, is a much simpler matter. We can then talk about how to collect the relevant information from the owner, i.e., how to go to Rentrak and learn who the identifier is for. By breaking down a huge problem into much smaller ones, the problem becomes solvable.

Fox has a way to go before putting all of these pieces together. But it deserves some applause for taking the first steps.

DCI and NIST

The impact of the problems posed this year by the National Institute of Standards (NIST) is indicative of a flawed concept of the DCI specification: reliance on a security specification body that has no connection with the motion picture industry. NIST’s actions pose substantial problems for the entire digital cinema industry, which if not addressed properly, will be quite costly. (See dci-and-nist-the-continuing-saga.) To summarize the problem: after 31 December, 2010, interoperable digital cinema equipment will no longer meet FIPS 140-2, as called for in the DCI specification. Further, any equipment manufacturer attempting to obtain FIPS certification for its product from 2011 onward will end up with a product that is not interoperable with existing digital cinema systems. The DCI spec will become obsolete if only because it will contradict its own requirement to be compliant with FIPS 140-2. It’s a messy situation.

Up until June, no public statement had been made by DCI regarding the changes by NIST. However, representing DCI, Wade Hannibal of Universal submitted a written comment to NIST concerning the changes, which was posted by NIST in June on its web site. Click here for the DCI comment. Click here for a full set of links to NIST documents, including the full set of comments and the June revision to Draft NIST Special Publication 800-131.

The approach taken by DCI in its comment is to get NIST to give it a few more years before implementing changes. The comment refers to the idea of republishing the older specifications without the support of NIST, as suggested in last month’s report. Wade writes in his comment:

DCinema product manufacturers have further expressed concern over the cost of recertification at a time when significant costs have been expended in becoming initially compliant to this new set of world standards. Thus, DCI is currently of the mind that unless the existing requirements can be allowed to survive an additional two to three years beyond the pending sunset dates (end of 2010 for FIPS certification), we believe our only path is to internalize the current FIPS specifications, and devise a method to use them for the next several years.

In response to the comments received, NIST revised its Draft NIST Special Publication 800-131 in June. In the revised draft, beginning in 2011, it deprecates for three years, rather than obsoletes, the use of the SHA-1 hash algorithm. This algorithm is used as a message integrity code (MIC) for every frame of picture and sound, a requirement of the DCI specification and of SMPTE 429-6 MXF Track File Essence Encryption. DCI also requires that the asymmetrical public and private keys which comprise the cornerstone of security key management in digital cinema be created using the method described in ANSI X9.31 Digital Signature Using Reversible Public Key Cryptography. NIST, beginning in 2011, now deprecates for 5 years, rather than obsoletes, the use of ANSI X9.31.

But a third and important item is not addressed, that in which NIST will no longer allow a key to be used for more than one purpose. This last area affects more than one area in digital cinema. Content encryption relies on the use of a 128-bit key to encrypt both the data and to generate the MIC of each frame of picture and sound. If it didn’t use a single key for this purpose, then the KDM would have to encrypt and carry two keys for every one it carries today. Even if two keys were to be carried, the equipment wouldn’t respond correctly. Digital cinema equipment is not designed to decrypt and use separate keys for content decryption and content integrity checks. In addition, digital cinema equipment uses the private key of the media block to decrypt the keys carried by the KDM, as well as digitally sign security logs. This also counts as multiple use of a single key. As of 2011, NIST will continue to disallow all of the multiple uses of a single key found in digital cinema.

Sadly, DCI is gambling that NIST will listen to the needs of the motion picture industry. It isn’t apparent that this is happening. Studying the comments, the changes made by NIST appear to be in response to comments made by companies such as Cisco, Motorola, and IBM, rather than DCI. When it comes to the use of keys for multiple purposes, DCI stands alone. It’s unlikely NIST will bend over for the motion picture industry when Cisco, IBM, and others aren’t also complaining.

NIST has clear responsibilities cut out for it, which do not include the motion picture industry. In its own words, from FIPS 140-3 (the successor to 140-2):

This standard is applicable to all Federal agencies that use cryptographic-based security systems to protect sensitive information in computer and telecommunication systems (including voice systems) as defined in Section 5131 of the Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996, Public Law 104-106 and the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002, Public Law 107-347. This standard shall be used in designing and implementing cryptographic modules that Federal departments and agencies operate or are operated for them under contract.

DCI needs a Plan B, and it’s running very short on time. It has 6 months…and counting.