In January 2010, NIST published changes to the FIPS 140-2 Security Requirements for Crytographic Modules upon which the DCI specification relies for its core security specification. Comments were requested from all affected industries, and upon evaluation of the numerous responses, including that of DCI, NIST revised its changes as follows:

- The SHA-1 hash algorithm will be limited in its use after 2013.

- The method described in ANSI 9.31 cannot be used as a random number generator for generating content keys after 2015. This method is specified by DCI for use in generating the symmetrical key for content encryption.

- The key pair used for a digital signature cannot be used for other purposes in new media block designs beginning in 2011. At the time, DCI required the re-use of the media block key pair for AES key encryption in the KDM, for establishing TLS sessions, as well as for signing security logs.

Item 1, which requires the disuse of the SHA-1 hash algorithm, is only limited to its disuse in digital signatures. Fortunately, SMPTE standards call for use of the SHA-256 algorithm in digital signatures. SHA-1 is specified in SMPTE standards for use in other digital cinema applications, but per NIST Special Publication 800-131A, released in January 2011, titled “Transitions: Recommendation for Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths,” all uses of the SHA-1 algorithm in digital cinema are allowed.

Item 2 does not impose a difficult problem. DCI has until 2015 to enforce it, and the revision only affects how mastering systems generate symmetrical keys, and not how projection systems are designed.

Most worrisome was item 3, with an implementation date of 2011. The change had the potential to affect how the KDM was generated, which in turn would impact how all servers in the field interpreted the KDM. No one expressed more panic than your author that DCI had allowed itself to be sucked into some ugly muck at a time when the digital cinema rollout was getting into high gear.

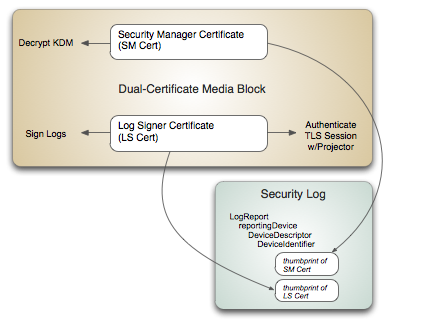

Thanks to a clever suggestion by Bill Elswick of Entertainment Technology Associates (and former CTO of Avica Technology), DCI managed to sidestep disaster. The trick was to accommodate NIST’s requirement for two certificates in new media block designs, while not impacting the manner in which KDMs are generated. Bill’s suggestion was to record the thumbprints of the required pair of media block certificates in the security log. KDMs continue to be unlocked by the primary Security Manager Certificate, called SM Cert, while the new Log Signer Certificate, called LS Cert, performs the duties of signing logs and TLS sessions. DCI specified the technique in its latest “errata.” The arrangement is illustrated in the figure below.

For now, DCI will squeak by the recent changes of NIST to its 140-2 specification. NIST has yet to announce its long anticipated transition plans to the newer FIPS 140-3 specification. But this transition is not expected to create new ripples.

However, NIST security specifications are guaranteed to again change, as older security algorithms become more fragile in the face of ever-increasing computational power. Eventually, there will be changes that promise to upset digital cinema systems everywhere. But by then, the current wave of senior executives in the industry will have retired. The problem will be left with young upstarts looking forward to promising careers. Hopefully, they’ll handle the mess they inherit by matching the cleverness and sheer luck of their predecessors.