The manufacturers of digital cinema equipment have a lot to share with the lovers of film. They’re each watching the best days for sales of their favorite technology fade away.

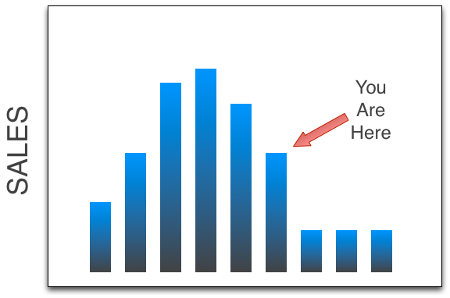

The total number of screens worldwide varies, depending on who one talks to. The number of modern screens that this author is aware of is in the order of 125,000. Some estimates of up to 140,000 have been heard, albeit this count appears to be based on B and C-grade screens found in India and elsewhere. Sticking to the 125,000 number, and estimating that 5% attrition will occur due to those unwilling to undergo the cost of conversion, leaves about 119,000 screens total. With about 25,000 of those left to convert, and a pace of installation of about 30,000 a year, it’s easy to see that the big surge of equipment sales will end this year.

Eventually, digital cinema equipment will have to be replaced, instigating new sales. The challenge for digital cinema projector companies is that their projectors are lasting a lot longer than they expected, possibly up to 15 years, or even more. Server companies are somewhat better off, as their products will have a lifetime in the 5-7 year range. However, integrated media blocks (IMBs) are unlikely to require such frequent replacement, with their external storage units being the only component that will wear and require early replacement. With the majority of projectors installed being the Texas Instruments Series 2 type, even if an external stand-alone server requires replacement, it will be an IMB that replaces it, again having a long life.

Replacing older Series 1 projectors will require more time than many may have thought. Cinedigm installed perhaps the largest share of Series 1 projectors in its Phase 1 rollout of 4000 screens – which also was the earliest rollout of scale, making these screens the most likely to trigger replacement purchases. These systems were financed through securitized loans, which will not be paid off until around 2020. If one were to attempt to pay these off today, the present value of the security will be found to be greater than the street value of the equipment, creating a barrier for changing out the projectors early. For this reason, the safe bet is to assume that it will take until 2020 for the replacement market to get into gear, and could take until 2025 or beyond until the replacement market heats up.

In the meantime, companies need to survive, and we’re seeing different strategies underway to achieve this. We limit this discussion to the projector companies:

Sony did as expected. Once its VPF rollout period ended, it announced the end of its stand-alone cinema sales division, folding it into its commercial projector division. Sony hasn’t given up selling its cinema projectors, but its worldwide sales are only a trickle today. Its product is costly and difficult to sell. Its commercial projector division will be saddled with the cost of maintaining the installed base of Sony cinema projectors until about 2022, when the VPF term for its US projectors will expire. Without sales, it’s unlikely that Sony will further develop its cinema projector, if it sticks around in this market at all. To back up that bet, last month Sony laid off its entire San Jose development group responsible for making its projector DCI compliant. The probability is high that Sony’s cinema product category will die between now and 2022.

NEC folded its cinema division into its commercial projector group a few years ago. Its product is competitively priced, but it does not sell projectors at the same volume as its DLP competitors. Because its projectors are DLP-based, the company will not be saddled with excessive costs when servicing extended warranties. It has not attempted to expand its cinema product base beyond projectors, sticking to core competency. Remaining alert to market trends, NEC has developed lower cost products to address the late adopter market. The only question for NEC is if it will choose to stay engaged in a low volume cinema market that’s likely to last for the next seven years.

Christie Digital has taken a very different approach from its competitors. Looking ahead to bleak sales, it’s taking the vertical approach to cinema, not only selling projectors with an IMB of its own design, but selling sound systems as well. The company has positioned itself as a one-stop shop for cinema sales. It has aligned itself with Arts Alliance Media for its TMS, although rumors on the street say the relationship has become strained. Its new vertical nature has isolated itself from Doremi, which has servers or IMBs in around 50% of the world’s cinemas. It also burdens the company with new R&D costs, such as making its IMB compatible with Dolby Atmos. If future sales are largely for new construction, and Doremi, GDC, and Dolby remain brands that exhibitors like, then taking the vertically branded route may not pay off for Christie. Its sound systems, for example, are unlikely to be considered top notch. But it’s a risk that Christie is obviously willing to take.

Barco also broadened its cinema product base, but in a manner that targets the high end. It co-partners with Doremi and GDC, selling their IMBs directly though Barco sales. By doing so, it has leveraged its relationship with GDC to sell into China, and its relationship with Doremi to sell to the rest of the world. It took a different route with audio, selling the high-end Auro 3D sound system, while leaving the door open for lower cost 5.1 sound system suppliers, as well as Dolby Atmos. It also positioned itself on the low end, now selling a low cost projector into the Indian market. Barco acquired the software division of former XDC, but has yet to introduce a cinema software product into the market. If there was a theme to Barco’s moves, it’s that the company is positioned to sell to the new build market, which is where the market will be for some years to come.