The rush to standards for immersive audio is fraught with so many problems that it’s difficult to document them all. Immersive audio is an area alive with innovation, innovation that could be stifled by subjecting it to standards in its formative days. This report discusses the innovation mechanism that object-based sound offers that can strongly differentiate the cinema experience from consumer systems.

Of the two immersive cinema sound formats on the market, one is 100% channel-based, and the other makes use of object-based sound. To a buyer, the distinctions are simple: channel-based sound requires a specific speaker array to preserve creative intent, while object-based sound, in its most ideal form, requires tight coupling between a rendering engine and a speaker system to preserve creative intent. Not all rooms are created equal, and a well-designed rendering engine will do its best to compensate for unusual speaker placements that can occur. The art of installing a channel-based system relies on skill in the selection and placement of speakers in the auditorium. While the art of installing an object-based sound system relies further on the capabilities of the rendering engine, and the art of setting it up. Proponents for object-based sound will pitch that the addition of the rendering engine allows a degree of flexibility that’s not possible otherwise. In making these points, I’m not pitching one method over another, but simply pointing out the differences.

Regardless of one’s beliefs about channel-based versus object-based sound, the entire entertainment industry is moving down the object-based sound path. MPEG is actively pursuing a consumer format it calls MPEG-H that will embrace both channel-based and object-based sound for consumer applications. As an example of its earnestness, this month, MPEG selected Fraunhofer’s proposal for MPEG-H as its basis for further development of the standard.

Sound for large listening environments, i.e. cinemas, deserves special attention over sound for small listening spaces, such as consumer applications. Replicating a sound field in a small listening environment is a lot easier than in a large auditorium. A technique employed by sound engineers to gain more control over the mix is to pan within sound zones. This is simple feat with channel-based sound, where speaker locations provide the sound mixer with natural zoning. In contrast, pure object-based sound has no natural zones. At its simplest, object-based sound treats the entire room as one zone. For large listening environments, better definition is achieved through zoning.

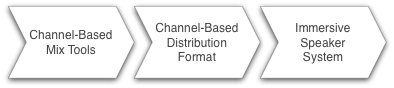

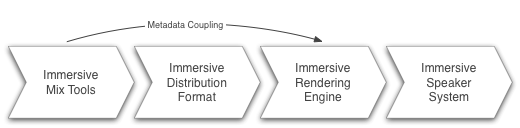

Channel-based and object mixes convey creative intent to the cinema auditorium in different ways, as illustrated in the diagrams below.

Figure 1. Preservation of Creative Intent With Channel-Based Mixes.

No coupling exists between the channel-based mix tools and the immersive sound system in the cinema auditorium.

Figure 2. Preservation of Creative Intent With Object-Based Mixes.

Metadata coupling is required between the immersive mix tools and the immersive rendering engine.

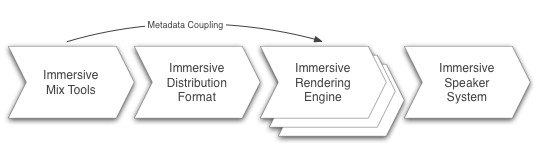

Figure 3. Preservation of Creative Intent with Object-Based Mixes and Zones.

The rendering engine must be capable of defining sound zones that match those created at the time of the mix. This requires specialized coupling between mix tools and the rendering engine.

It’s easy to see from the illustrations above that channel-based mixes are the simplest to manage in distribution. Object-based mixes, on the other hand, require close attention to the coupling between mix tools and rendering engine, and the coupling must be carried in the distribution format. Simple rendering models focus on the geometric placement of sound across the speaker system. More complex mix tools and rendering engines provide specialized techniques that allow the mixer to define spatial sound zones somewhat independent of speaker locations.

Complex rendering methods are useful for speaker systems that incorporate a large number of speakers in large cinema auditoriums. It’s reasonable to assume that methods for consumer object-based audio are not focused on commercial cinema applications, but on environments where simple rendering methods will do the job. DTS MDA, for example, is a simple object-based format designed for the home. Dolby Atmos, on the other hand, was designed specifically for cinema. DTS has not developed a set of mix tools for MDA that has been put to work in motion picture production. Dolby, on the other hand, has jumped through hoops to satisfy motion picture mixers, going as far as purchasing IMM Sound for its set of well-developed mix tools. While Barco may have no investment in mix tools, it relies on Auro Technologies for this. Auro Technologies has a substantial investment in a set of mix tools that also have been used in motion picture production. Auro plans to introduce a set of mix tools that incorporates MDA.

If all of this sounds confusing, then I can reduce it down to this: rendering engines are not created equal. Some are basic, some are complex, with the more complex engines designed for better control of sound in the cinema. Where there is complexity, there is intellectual property. If the industry wants a simple format intended for home distribution, then such a proposal is available through DTS. NATO certainly seems to think this is good enough for its members. A more sophisticated approach that better addresses the preservation of creative intent in the cinema is also available from Dolby, but it involves intellectual property. A third object format is likely to be introduced by Auro, incorporating its intellectual property within the DTS MDA format in a yet-to-be-disclosed manner.

By standardizing at this early stage, the industry will either freeze innovation at a level that is intended for home distribution (unlikely), or standardize a base level, on top of which competitors add their intellectual property (more likely).

The introduction of intellectual property through object-based sound appears to be unavoidable. On the bright side, it also appears to be highly desirable. Cinema thrives on innovation, and any effort to stifle innovation isn’t in the industry’s best interest. Unfortunately, this isn’t how distributors and exhibitors are thinking today. Without taking time to understand the nuances of object-based sound, and the intellectual property that makes it useful for cinema, the industry is charging down a path that will only lead to disappointment.