The first meeting of the SMPTE 25CSS Working Group for Interoperability of Immersive Sound Systems in Cinema took place this month. The calm and organized demeanor of the meeting belied the chaotic thinking of its membership. Some standards groups get by running themselves, but this group clearly will require strong and insightful leadership by its chairman if it is to achieve anything meaningful. Rather than discuss what was said in the meeting, which technically one isn’t supposed to do (there will be meeting minutes for SMPTE members for that), it’s more interesting to talk about what wasn’t said.

Not so surprisingly, this was a meeting where attendees could not see the forest for the trees. But this is not to be unexpected. 25CSS is the first standards group concerned with digital cinema to sprout outside of the 21DC camp. A good number of its members, and most certainly its leaders, were not responsible for creating the digital cinema standards that built this industry. These neuf members may think of themselves as rising stars, but the older crew often look upon them as dazed and confused. Adding to the messiness, immersive sound is a difficult subject to discuss, not because it’s difficult to understand, but because few actually stand back to grasp the big picture.

This could be seen in the willingness to dive into details without a serious discussion of what the group can actually accomplish. While MDA is highly advertised, it also is the most under-capitalized effort in the history of media to establish a new sound format. In its eagerness to demonstrate that it’s a viable force, MDA proponents jumped forward with detailed design concepts. No time was spent discussing how these concepts map with the two commercial formats in the field. MDA proponents, for example, would like their own synchronization signal. Apparently the one Dolby is standardizing (in SMPTE 21DC) doesn’t work for them, for reasons not explained. In fact, it’s not clear why MDA proponents didn’t redline Dolby’s document while in committee in 21DC to better suit their application. It would have been of much more benefit to the industry to collaborate on a single synchronization signal that works for multiple applications rather than have every application propose its own.

The MDA camp also talked of a “reference renderer.” It wasn’t clear to most people, however, as to what purpose a reference renderer would serve unless one could listen to it. Which raises questions such as who would listen, and who would judge compliance? Considering that 25CSS has a substantial membership that’s stumped over the role of “X-Curve” when setting up a sound system, and that SMPTE does not monitor compliance of its standards, this didn’t seem like a very smart place to go.

Admirably in contrast, Auro and Dolby refrained from putting forth documents that would compromise the other, sending a signal that they’re more interested in dialog. It is dialog, however, where this meeting was most lacking. While the chairperson is adept at leading a civil meeting, he has further to go to demonstrate the degree of insight needed to guide this group. In a move that could have been better, the chairman presented a complex and confusing task diagram, understood by no one, outlining the decision paths that the group could pursue. The best response was some gentle guidance suggesting that a production workflow diagram for digital cinema sound might be more useful.

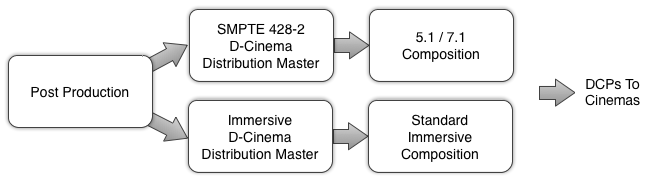

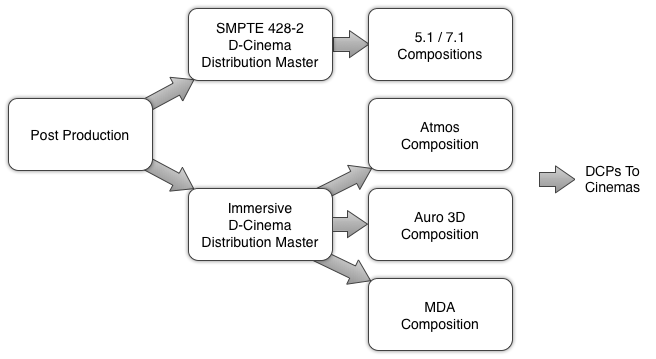

Production workflow is an area where this group could make its mark in a very positive way. In 5.1/7.1 audio, digital cinema workflow embraces the intermediate concept of the Digital Cinema Distribution Master (DCDM). The illustrations below in Figures 1 and 2 how an Immersive Sound DCDM would fit into the production workflow.

Figure 1. The Holy Grail of Immersive Sound Workflow

Figure 2. A Practical Immersive Sound Workflow

SMPTE 428-2 defines the characteristics of the DCDM for up to 16 channels of sound today, essentially a bunch of uncompressed WAV files, each channel having up to 24 bits of audio. One would expect that an Immersive Sound version of the DCDM would also be a collection of WAV files, with added time-dependent metadata. It should be fairly simple in concept, and thus fairly easy to standardize. Most importantly, the establishment of an Immersive Sound DCDM would satisfy nearly all, if not all, of the ills that the industry seeks to fix. DTS and Auro 3D would get access to Dolby Atmos mixes. Dolby would get access to Auro and DTS mixes, and everyone is happy.

Or nearly everyone. No solution is perfect, and the Immersive Sound DCDM would bring with it a new set of problems. Whether or not these problems can be absorbed by the industry will be discussed in a future report.