It’s difficult to have a conversation about 3D screens without RealD entering the discussion. RealD, however, is facing its share of challenges, not the least of which is the potential of a hostile takeover. Its licensing model is not sustainable. Exhibitor spreadsheets indicate it’s cheaper to buy than to lease. RealD’s 3D cinema technology is no longer a monopoly. The company is facing stiff competition, which it is attempting to eliminate by claiming patent infringement. (Consider how successful this strategy has worked for Apple with Samsung.) While the threat of lawsuit was enough to cause Volfoni to back down, it didn’t stop MasterImage from charging forward this month, filing an Inter Partes Review (IPR) with the US Patent Office to invalidate RealD’s light-doubling patents. But if there is an area where RealD may have claim to true innovation, it is in its screen technology. And even here, RealD’s ability to stand out appears to fall “flat.” (Please forgive the pun.)

Polarized 3D requires metallic screens to preserve polarization of light, which is required for polarized glasses to appropriately direct left and right images to the eyes of the audience. While the name “silver” is the marketing term used, the metal commonly employed is aluminum. Aluminum flake powder has many industrial uses, providing a wide market that keeps cost down. Alternative manufacturing methods raise the cost of the particle, which must be taken into account in real-world applications. RealD’s contribution is a process for the production of engineered aluminum particles and the coating of these particles onto screens. The result is its “Precision White” technology.

While RealD has a patented a process for engineering particles, it doesn’t own the process for manufacturing screens that use its particles. So far, only MDI has developed a process for manufacturing such screens, comprising its HighWhite screen line. The expense of MDI’s RealD screens, and the limitation of sales to RealD installations, has not contributed to its popularity among exhibitors. However, the technology has proven to be immensely popular among screen manufacturers, who are bending over backwards to beat RealD with more affordable, high performing products. Underscoring the unaffordability factor, MDI developed its own in-house competition to its RealD HighWhite line to better capture sales. But Harkness is in the game, too, and not to be dismissed.

The competition for high performance 3D screens can’t help but benefit exhibitors, but the surprise is that it took so long for the screen companies to wake up. The screen companies are the secret benefactor of 3D movies, as silver screens have a replacement cycle measured in years, producing a nice flow of recurring revenue, while flat screens have a replacement cycle measured in decades. Thus, its smarter to drive sales of 3D screens, and this warrants research to provide better products.

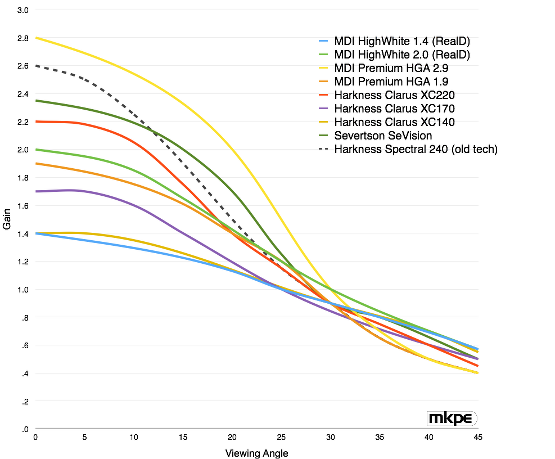

By simply studying graphs on websites, it’s not obvious how far silver screens have advanced, or how the different makes and models compete. Wide viewing angle being the feature most sought after, the chart below graphs viewing angle of new generation silver screens. To see how they measure up, MDI’s HighWhite (RealD) screens are included in the chart for comparison, along with the old stalwart of silver screens, the Harkness Spectral 240. As you can see, the Harkness Clarus XC140 exhibits a nearly identical viewing angle as the MDI HighWhite 1.4 (if not slightly better), and MDI’s own Premium HGA 1.9 matches the HighWhite 2.0 up to 25 degrees. All of the screens shown have a wider viewing response than the older Harkness Spectral 240.

It’s unlikely that research in improved screen performance will stop here. Once the R&D bug has taken root, better ideas are likely to emerge. RealD may not be realizing an ROI for its efforts, but it should be thanked for kicking a sleepy industry into gear.