The good news in immersive sound is that a draft document that defines the many parameters of object-based sound, what I refer to as the object model, has been completed in SMPTE. That doesn’t mean it’s approved. But it’s a milestone nonetheless. The question on everyone’s mind, however, is what does this mean?

The difficulty in achieving agreement on a useful standard will be determined by Dolby’s strategy for Atmos. Dolby is not only the leader in object-based sound in cinema, it remains the only company to deliver object-based sound in cinema. While DTS made a big marketing splash with its MDA object-based format over the past few years, it has yet to deliver a movie sound track. If DTS is waiting for standards to materialize before moving forward, it could be waiting a long time. Auro and Barco are also in this game, but have made less noise than DTS about object-based audio.

While this scenario would suggest that Dolby’s best play would be to delay standardization and continue to grab market share, this is not at all evident in its actions. Dolby, being the only company with substantial experience in object-based sound, has contributed substantial knowledge to the object model work in SMPTE. If one were to expect Dolby’s collaboration to continue in this manner, then a standard could pop out of the oven in another year or two.

Or not. The accomplishment recently achieved, having taken a year, is the easiest of the several tasks required to produce a useful standard. Ahead lie the tasks of determining the architecture of the system, and the elements of that architecture that require standards for interoperability at the distribution and exhibition levels. But there are fundamental differences between the numerous Atmos systems that Dolby has deployed and the theoretical MDA systems that DTS proposes.

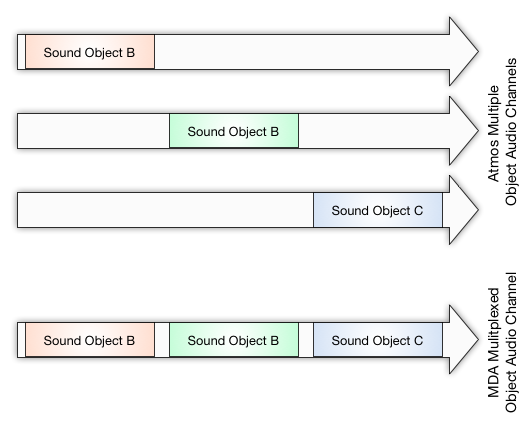

These differences are most evident in the architecture of the formats, as illustrated below.

Sound objects (remember, these can be thought of as “sound bites”) are carried differently in the two formats. Dolby allows up to 128 object audio channels for the carriage of sound objects, each sound object occupying a full-length audio channel. DTS proposes a more compact method of carrying sound objects by multiplexing them in much fewer object audio channels. In the illustration above, three audio object channels are shown for Atmos and only one object audio channel shown for MDA, both carrying the same object sound content.

Dolby’s method may seem inefficient, but it compensates by compressing the audio with Meridian Lossless Packing (MLP), reducing the size of each channel by effectively eliminating the empty space and lightly compressing the audio. MLP is the heart of Dolby TrueHD@reg; compression, used in Blu-ray discs. DTS proposes to use no audio compression while reducing file size using its multiplex scheme. Of course, DTS has not, and undoubtedly cannot, without punishment from its investors, license MLP from Dolby.

The forthcoming dialog in committees is predictable. Dolby: “Atmos with MLP is implemented in 1000 (or thereabouts) screens, and works. Our experience is that objects may overlap, and that the flexibility of our method does not tie the hands of mixers. The proposed alternative is an invention that has not been tested in mixing rooms or theatres.” DTS: “MDA offers a license-free alternative that uses uncompressed PCM audio and can be carried in the 16-channel audio track file of an unmodified DCP. We believe it provides adequate flexibility for sound mixers.” Please note that these statements are my conjecture, and not quotes from the companies named. However, I will take bets that we will soon hear them.

There are a few outcomes that are possible in terms of standards. None of which are important to discuss at this time. More important is the strategy that is likely to be in play. Whether or not Atmos is fully standardized is irrelevant. DTS will not license MLP. If MDA emerges as a standard, then the question is whether anyone will care. Even if exhibitors rush to install MDA in cinemas, it’s unlikely that this will deter Dolby from continuing to sell Atmos as it is today, with the result that multiple immersive sound systems will exist. Distributors and exhibitors will complain that this is not what they want. But they will learn to bear it, just as they did with the mess of multiple digital sound formats for film in the 90’s.

The decision that matters most in immersive sound is that of the filmmaker. Will they mix sound for Atmos, MDA, or both? One can imagine mixing for Atmos only, for purity of sound, or mixing for both Atmos and MDA, for maximum footprint. Presumably, only a budget-conscious movie will pursue an MDA-only mix. It’s entirely possible that Dolby will be bold and not accept an MDA-only mix on Atmos systems. Given that Dolby is likely to be top choice in the decision tree, its mixing tools will also be top choice in the studio. To hold that position without compromising standards is not hard. Dolby’s tools simply have to provide a standards-compliant object-based audio output (presumably MDA) for non-Dolby systems. This would explain Dolby’s keen participation in establishing the standardized object audio model. The object model is the only part of the standards effort that Dolby need to concern itself with, as it plans to implement it as a secondary output. As pointed out in October 2013 in Would Someone Speak Up About Where Immersive Sound Is Going, the real battle of immersive sound will be in the mixing room, not in a standards committee.