X-Curve is the name given to the frequency response curve applied in all cinemas today. In an era where relatively cheap real time analyzers (RTAs) arrived in the hands of not-always-well-trained technicians, X-Curve was applauded. Aligning a cinema to X-Curve on an RTA produced far better results than when an inexperienced technician attempted to align to a flat line. (If you ever have the ability to try this, you will quickly understand what I mean.) But as time passed, X-Curve became a target curve, whether needed or not. It once was the case that cinema sound mixes were presumed to be flat, without spectral coloration. But today, the evidence is mounting that this is no longer the case, separating cinema sound, which is now considered colored by a growing cadre of experts, from the body of other media sound, which no one would object to saying is intended to be uncolored, or flat. Several studies were published over the past year and a half on cinema sound and X-Curve, providing an opportunity to review this subject yet again.

Cinema sound has a history of frequency response curves. Ioan Allen, who drove Dolby’s entry into cinema in the 70’s, authored an informative article titled “The X-Curve: Its Origins and History” which, among many things, describes the history of cinema response curves. One of the challenges for Dolby in its early days of cinema development was the extreme rolloff in frequency response applied to cinema sound systems. The sharpness of the curve is a hint as to the quality of sound systems in those days. ISO was seeking to standardize a response curve for cinema, and in the end, it standardized two. N-Curve, for normal, and X-Curve, for experimental. X-Curve was the improved curve proposed by Dolby. It had a high frequency rolloff of -3db/octave starting at 2KHz, a significant improvement over N-Curve.

At the time, and for many years after, it was assumed that the rolloff in room response captured in X-Curve was caused by room reverberation. Sound is thought of in terms of “steady state” response and “direct” response, or “first-arrival.” First arrival refers to the sound the ear first hears, as opposed to the steady state sound heard over time, which includes room reverberation and reflections. First arrival is most important, as our brains identifies the direction of the sound on the basis of first arrival, regardless of room reverberation from walls and ceiling. The measurement of first arrival sounds, without interference of reverberant sounds, was not easily possible at the time of Dolby’s entry into cinema. The readily-available technology of the day was the Real Time Analyzer, which measures steady state response. X-Curve, up until recently, had always been associated with the steady state response of a room. Accordingly, the belief prevailed that the rolloff of X-Curve was a product of room reverberation against an otherwise flat signal.

However, time has passed, and technology has advanced. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) measurement tools are now (and for some years) readily available. With an FFT measuring device, a very short “chirp” is played through the loudspeakers, short enough in time such that the measurement time window can exclude any room reverberation and reflections from the measurement. In short, FFT is a good tool for measuring first arrival sound. It works well for frequencies high enough where the first arrival signal can be separated from the room’s steady state response, typically a few hundred Hertz. In October 2014, SMPTE published an extensive report titled “TC-25CSS B-Chain Frequency and Temporal Response Analysis of Theatres and Dubbing Stages.” It is perhaps the only published study to compare RTA measurement with FFT measurement of the same auditorium. One of the observations in the report is that the frequency response plots made by RTA and FFT were remarkably similar.

If the FFT is measuring first arrival sound, and RTA is measuring steady state sound, and the two measurements look similar, then one can conclude that the effect of room reverberation on the measured RTA response is minimal. Oddly, the SMPTE report overlooked that conclusion, simply stating that the FFT can be used in place of the RTA when calibrating a room to the X-Curve frequency response. But the inconsequential impact of room reverberation is quite significant. X-Curve was instituted to offset the impact of room reverberation when measuring with an RTA. Ioan Allen discusses this in his X-Curve article, and is consistent with my personal knowledge from my early days in Dolby working with Ioan. However, if rooms are now designed such that room reverberation no longer requires compensation when measuring response, then the question must be asked why X-Curve is still used?

This is where the waters divide. The argument for X-Curve is that it is now an accepted target curve, which both mixing room and cinema are aligned to meet. The argument against using X-Curve is that the mixing room and cinema could be aligned for flat response and get equally good if not better results. It would also put cinema recorded sound on par with recorded sound across the media landscape. Those against change are concerned for backwards compatibility. Those for change have yet to explore what the impact of a change would cause in cinemas around the world.

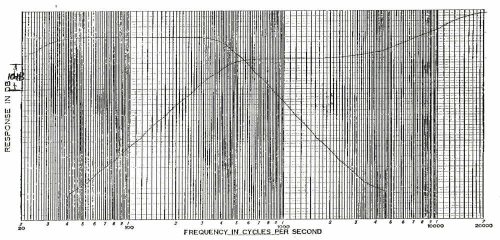

Among the confusing papers on this subject are the myths that have evolved. I was recently told by several people in important positions that X-Curve exists because of the rolloff caused by perforated screens. One went so far to say “our forefathers” did not understand the rolloff caused by screens, resulting in X-Curve. This is one of the most remarkable mis-understandings I’ve come across. The best example of the knowledge of our “forefathers” is the work of Tom Holman in THX during the early 80’s. THX approached the crossover, speakers, and screen as an assembly whose collective frequency response should be flat. It is well-known that perforated screens introduce a significant rolloff at high frequencies. The characteristics of that rolloff vary among screen products. THX chose a general screen compensation, consisting of a 6 db/oct boost beginning at 4KHz. The boost was built into the THX electronic crossover, designed to work with Altec A7 “Voice of the Theater” speakers, while providing compensation for the high frequency rolloff caused by the screen. Crossover, speaker, and screen were treated as a system. And the system was engineered to be as close to flat response as possible. There is a caveat in this, however. In the 80’s, headroom at boosted frequencies did not need to be over 6dB, due to the limitation in dynamic range of analog sound tracks. With digital cinema, headroom at all frequencies should be 20dB. That can be a challenge to achieve at boosted frequencies, although with modern multi-way speaker systems, it’s not as difficult as it would have been with the 2-way Altec A7.

A plot of the THX crossover frequency response from mid 1980’s

Today, we hear from experts who say they don’t need to compensate for the screen. Instead, the screen’s uncompensated high frequency rolloff is used to meet X-Curve as a target curve. That statement alone shows something has changed from the mid-80’s to now.

Unfortunately, changing it back does not appear to be a simple task. We have a new generation of sound engineers who think the rolloff of X-Curve is the norm for room alignment. This belief is underscored by work underway in SMPTE to use FFT measurement, a tool for measuring first arrival sound, to align rooms to X-Curve, which was originally intended to a measure of steady state sound.

The error has not gone unnoticed in the academic world. Some excellent papers have emerged in recent years that discuss the conditions for flat response in cinema auditoriums, notably from Floyd Toole, PhD, a now retired researcher from Harman (parent company of JBL), and Linda Gedemer, currently with Harman, listed below. Also listed below are Ioan Allen’s interesting review of the history of X-Curve, and the SMPTE B-chain report discussed in this report. One of the common themes in modern work is that there is little to be done with equalization at high frequencies other than compensate for the screen, and that the bigger problem is bass management. For those with time on their hands, enjoy.

Ioan Allen: The X-Curve: Its Origins and History

SMPTE: TC-25CSS B-Chain Frequency and Temporal Response Analysis of Theatres and Dubbing Stages

Floyd Toole: The Measurement and Calibration of Sound Reproducing Systems

Linda A. Gedemer: Predicting the In-Room Response of Cinemas from Anechoic Loudspeaker Data

Linda A. Gedemer: Evaluation of the SMPTE X-Curve Based on a Survey of Re-Recording Mixers