Metamerism is an odd problem that occurs in unnatural situations. If two people look at a flowering plant in sunlight, they will agree when describing the colors and shading. If the same two people were to look at the same flowering plant under certain artificial lighting, they are likely to not agree at all. The type of lighting that can cause such differences will exhibit an irregular spectral response, i.e., a spectral response that is not smooth over the range of frequencies seen by the human eye. It seems natural that the eye, being sensitive to three overlapping ranges of spectrum, will interpret colors differently when viewed using such lighting. But it is often considered a surprise that such differences in color interpretation will vary across a population of viewers. Laser illuminators, by their very nature, have a very unique and peculiar spectral response. Among the several problems that stand in the way of rapid introduction of laser illuminators, metamerism could be the least understood.

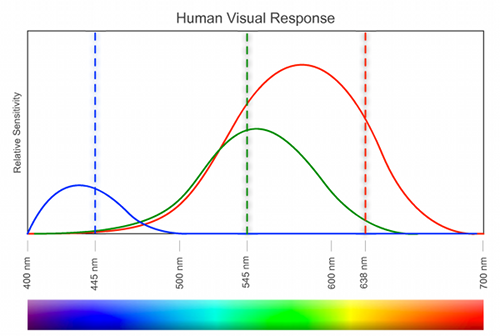

The problem is illustrated in the figure below. The spectral sensitivity of the human eye is plotted, showing three curves, each represented in a different color. Primary colors are used in the illustration to aid in understanding the role played by each range. The dashed vertical lines, in turn, represent the laser primaries of 445nm, 545nm, and 638nm, as disclosed publicly by Laser Light Engines, and used by Sony in its public laser projector demonstration at SMPTE TSC.

The narrow spectrum of laser primaries introduces a visual problem.

Achieving white light, the range of colors, and their proper shades, requires a sophisticated chroma look-up-table, or LUT. When light sources and filters are used that produce broad spectral footprints for the red, blue, green primaries, the settings in the LUT can be set with assurance that the proper colors will be seen across a large population of viewers. But when laser illuminators are used, the colors seen by one person are likely to be different than those seen by another.

What is most confusing about metamerism is that two different experts can have sharply different experiences when viewing the same laser illuminated projected image. Both experts will be correct in describing what they see, but their descriptions could be starkly different. In fact, such occurrences are a clue that metamerism is at fault.

I first experienced the impact of metamerism when viewing the Kodak laser projector in Rochester 1 1/2 years ago. Barry Silverstein, who led the project, explained the effect when I commented on a color shift that I was seeing. Bill Beck of Laser Light Engines attended the same demonstration, and I was at his facilities in Salem the next day, where he was able to further explain the phenomenon.

Laser illumination has a lot of secret sauce in it, and so manufacturers won’t spend a lot of time explaining their methods for solving problems, metamerism included. The basic concept for solving metamerism is to broaden the frequency range of each primary, which is not easily done with lasers. Laser speckle is often solved by modulating the frequency of a primary, but the degree of modulation necessary for speckle reduction is far less than that needed to correct metamerism. Another method would be to increase the number of primaries used, which also increases the complexity of the chroma LUT.

The rash of laser illuminator demonstrations in Las Vegas in March produced varying reports from observers. It is the variance that was notable. The culprit, of course, was metamerism.