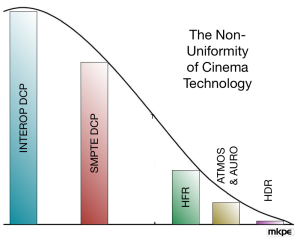

The digital cinema rollout brought cinemas everywhere to a uniform technology, for the first time in generations, and perhaps for the last time ever. In a competitive marketplace, non-uniformity wins. With that in mind, it would be smart to look at how to best manage it.

The DCP is a good place to start, with so much pain expressed about changing it. Having organized and led the team that developed the DCP concept in December 2001, and having authored the first documents and presentation about it, I’ll be the first to admit that it’s overdue for review. When we set out to solve the problem of content distribution, we undertook a number of problems to solve. Foremost was that filmmakers needed a concrete package that could be approved as a final product and to which copyright could be applied. We weren’t streaming content and we weren’t delivering a DVD with married trailers, so tools developed for the broadcast and consumer markets couldn’t be applied. We were looking at 100’s of gigabytes of information, so we needed the ability to organize it into manageable chunks. It was not uncommon for distributors to insert partial productions in the distribution pipeline while things such as product placement and credits were sorted out. With film, this process was handled by holding back, or simply replacing, reels of film. So temporal organization would best suit the business model. Sound tracks and subtitles would be distributed in different languages, so it would be efficient if certain elements such as picture data could be reused. This required modularity. The format had to be extensible, as we were certain some things would change.

All of these requirements were successfully addressed by the DCP concept. The concept is quite simple: each file of content contains only one essence type: these are called “track files.” Track files are organized temporally: these are called “reels,” borrowing the term from film. Conceptually, there is no limit to the number of track files required for a movie, and no limit to the number of reels. In practice, limits are applied. New track file types can be introduced at any time without breaking the structure, meeting the need for extensibility. Track files are organized by means of a playlist, called the “composition playlist.” The entire content work, which is approved by the filmmaker and carries the copyright, is called a “composition.” (A point of history – the name “composition” was coined by Mike Bruns, who was with Grass Valley at the time).

Looking back with the wisdom of time, our focus for addressing change was limited to the content domain. We didn’t consider the need to address a change in technology for the DCP itself. As a result, the industry finds itself attempting to introduce newer versions of track files and CPL through the mechanism intended for content change. A different version of the DCP is created for each new technology revision, even though each new DCP so created represents a duplicative version of the digital work. This is unnecessary from a creative and business point-of-view, introducing numerous inefficiencies that create friction.

A classic example is the subtitle track file (also known as a caption track file). For historical reasons, there are two technologies used to describe subtitles in digital cinema: CineCanvas (SMPTE RDD 20), and SMPTE ST 428-7 Subtitles. Not all equipment in the field can read SMPTE ST 428-7 subtitles, but CineCanvas will work everywhere. A problem exists because the industry now wants to distribute 428-7 subtitles everywhere. Further, the subtitle problem is compounded by lumping the introduction of 428-7 subtitles with changes in other track files and the CPL itself (altogether comprising the revised DCP called SMPTE DCP). To underscore the earlier point: the switch to 428-7 subtitles (as well as the switch to SMPTE DCP), represents only a change in technology of the distribution, and not a different version of the motion picture work that the DCP defines.

There are better ways to manage technology change. To more easily illustrate the concept I wish to introduce, I will focus solely on the change to distribute SMPTE 428-7 subtitles. Since 428-7 subtitles cannot be read by all equipment, but most certainly can be read by new equipment, then it’s only a matter of time before old equipment is replaced with newer more capable equipment, allowing 428-7 subtitles to play everywhere. But distributors worldwide could be waiting a very long time for this to happen. The subtitle issue is particularly difficult, as it cannot be fixed simply by software. Even if it could be fixed by software, there would still be the software upgrade cycle to consider.

To put the software upgrade problem in a familiar context, consider the number of users of the Microsoft Internet Explorer 11 browser versus that for other versions of Internet Explorer. IE 8 was released 4 1/2 years prior to version 11, and versions 9 and 10 released in-between. Presumably, the equipment on which the browsers are installed is connected to the internet (a good reason to have a browser), which should facilitate the ease of upgrade. But according to NetMarketShare, the number of users of IE 11 browsers today is only 42% of the total market of IE users. IE 8, the oldest browser of the lot, has a whopping 34% of IE’s market share. (If one thinks this analysis is skewed to favor my point, I would disagree. If the market share of IE 8 was 0%, the total IE market share of version 11, the latest version, would be much closer to 100%.) The point is that there are more factors that impact the upgrade process than mere availability of the upgrade. If anyone thinks digital cinema is going to experience faster upgrades than Microsoft scores, I believe they’re in for a surprise.

A more effective way to address technology change in the DCP, than reliance on universal transformation through upgrades, is through the prioritization of track files. If both CineCanvas and SMPTE 428-7 subtitles were to co-exist in the same DCP, then distributors would be relieved of the burden of multiple distributions to accommodate both technologies of subtitle. The DCP itself would still represent a unique digital work, but the inefficiency of duplicative works would be avoided. Another boon would be that owners of newer and upgraded equipment would be rewarded with the ability to exploit advantages offered by newer subtitles, such as stereographic subtitles, an upcoming feature of SMPTE 428-7. At the exhibitor side, the prioritization process would be simple: play the newest technology of track file available in the distribution which the system can utilize. For example, if a system could read SMPTE DCP distributions, but was unable to play SMPTE 428-7 subtitles, then it could revert to the CineCanvas track file in the distribution.

While the mention of SMPTE DCP in the above example will no doubt raise smiles, the more effective scheme would be to first add track file prioritization to Interop DCP. It would avoid the risks associated with other baggage carried by SMPTE DCP, i.e., the small differences in CPL XML and track file MXF wrapping that can break untested systems. If the new DCP is properly constructed, the older system that has never been upgraded and ignorant of SMPTE 428-7 subtitles will ignore it in favor of the subtitle track file that it does know. Newer and upgraded systems would be able to take advantage of the newer track file. Understanding that the need for distributors to support Interop DCP will continue for a very long time, the concept of track file prioritization would allow distributors to introduce new features without breaking old systems, and doing so without adding more DCPs and KDMs to manage. In the manner in which the industry is approaching technology change today, without track file prioritization, distributors will be required to distribute the same work in two different technologies of distribution package, a scheme fraught with inefficiency and prone to error, in order to take advantage of something as simple as 3D subtitling.

Track file prioritization for accommodating technology changes is a big pill for the industry to swallow. If done properly, it would require formalization of Interop documents: anathema to some, yet long overdue considering its use in 130,000 screens worldwide. The medicine is worth examining.