CinemaCon was host this year to demonstrations of three immersive sound systems: Atmos (Dolby), AuroMax (Barco/Auro), and DTS:X (DTS). Sound has never been more confusing to exhibitors, and more deceptively presented. Missing from CinemaCon was the core concept that separates cinema from home entertainment: preserving Creative Intent. None of the systems demonstrated were capable of playing a mix created on another system.

There is no end to the number of types of sound system that can be developed when adding metadata to sound. Claims of “my metadata is better than your metadata” simply fly over everyone’s head. If there is one area where the standards effort has risen to the occasion, it has been to put to bed the differences over metadata – the descriptors of a sound object. All three companies collaborated on a draft specification that appears to have consensus. But until a metadata standard actually emerges, consensus doesn’t mean much.

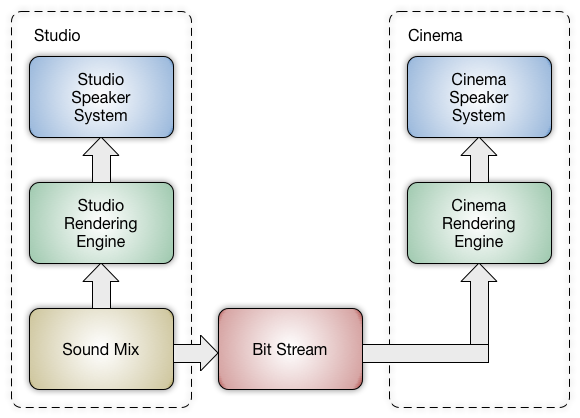

The next step in the standards effort is to define the method of carrying sound and metadata to the cinema. This is referred to as the “bit stream,” for various reasons. It’s not necessarily a simple step, as there are as many ways to define a bit stream as there are automobiles on the 101 freeway in Los Angeles at rush hour. To accelerate what could otherwise become a painful process, a few Dolby executives say their company intends to submit the Atmos bit stream for standardization, for use by all without royalties. If so, it would greatly simplify the standards effort, and eliminate the scenario described last month where dual distribution would rein. (Dual distribution would be required to support the Atmos bit stream and a non-Atmos standardized bit stream.) Standardizing the Atmos bit stream would produce as good a result in distribution as one could expect.

But such an immersive sound standard won’t solve everything, particularly the preservation of creative intent in cinema. Dolby specifies one manner of speaker layout, with single row of speakers on the auditorium walls and two rows on the ceiling. With its new AuroMax rendering engine, Auro specifies a different layout, having two rows of speakers on the walls, and a matrix of speakers on the ceiling, with none quite in the same place as Dolby’s. DTS says it doesn’t care where the speakers are, which oddly enough, only adds to the confusion.

How is an exhibitor to decide on a system? The first rule is that the preservation of creative intent across multiple sound systems requires the buy-in of sound mixers. In contrast, all that exhibitors hear today is pitches from the sound companies. Importantly, no sound mixer has yet to say that a movie mixed on the speaker system and rendering engine of one company sounds acceptable on those of another company. But to be fair, no sound mixer has ever heard two sound systems driven by the same mix.

That could soon change. If Dolby standardizes its Atmos bit stream, and if one or both of Dolby’s competitors were to adapt to accept the Atmos bit stream, then comparisons of mixes across multiple sound systems could begin. Optimistically, what is mixed on one system will sound good on another. Realistically, the competitive system is more likely to be critiqued as inadequate in terms of preserving creative intent.

Can the System on the Right Preserve What’s Heard on the Left?

The standards effort will be most successful if Dolby were to standardize its Atmos bit stream. Such a magnanimous step would eliminate the potential of dual bit streams in distribution, an important efficiency. (Dual bit streams would be necessary to carry that of Atmos and that of a non-Atmos standard.) But it won’t eliminate the great loudspeaker confusion that will follow. If Barco/Auro and DTS were truly paying attention to the preservation of creative intent, they would shift their thinking about speaker placement as quickly as Dolby may be accelerating the standards effort.