In talks earlier this year given at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) to the European Digital Cinema Forum (EDCF), and another at the Beijing Film Festival Technology Forum (pardon my plugs), I veered away from the usual overview of new technologies and into the chasm of technology rollout in cinema. My point was that there is too much expectation of the role of standards and other authoritative entities, such as DCI, when it comes to rolling out a new technology. Technology rollout post digital transition requires different thinking.

Three examples come to mind that cover the gamut of rollouts, starting with the digital transition. The digital transition was conceived as a replacement for film technology that would deliver significant economic benefits to distributors. The transition was a one-time event, with unique and important roles played by DCI and SMPTE, and, of course, the Virtual Print Fee (VPF) subsidy.

The replacement of film projectors with digital projectors worldwide required an investment of around US$8B. Assurances were needed for financial institutions to pony up the necessary capital. Those assurances came in the form of a guarantee by studios to release films digitally, and assurance that the technology was stable. After all, Hollywood studios have a history of not getting in line when it comes to new technologies. (Remember HD-DVD and Blu-Ray?)

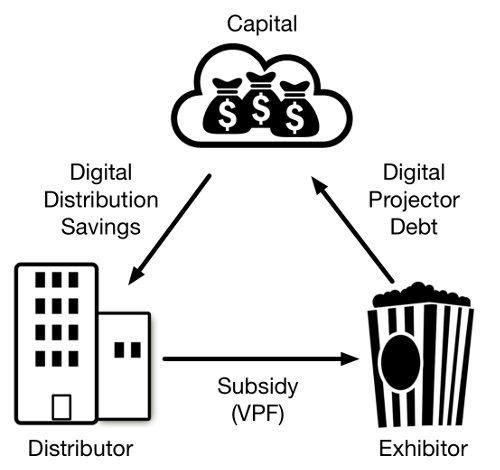

Several pillars in the transition provided these assurances. The DCI specification, and the DCI Compliance program, provided assurance that a secondary market for equipment would exist. Much of this work had its roots in more inclusive discussions that took place in SMPTE. Further, studios agreed to apply savings realized when shipping digital prints in lieu of film prints, called Virtual Print Fees, to help retire the equipment loans. So much of the cash was coming from strong, known companies. To tie the knot, only DCI compliant equipment could receive a VPF, ensuring that a uniform standard would rollout. As a result, the digital cinema rollout was an impressive success. The graphic below illustrates the simplicity and elegance of the financing mechanism.

The Digital Cinema Transition

(not to be repeated)

But the key elements that drove the success of the digital transition no longer exist. There is no longer a financial incentive for studios to subsidize the rollout of new equipment. (To those who think there will be another VPF: get over it.) DCI and SMPTE still perform useful roles, but not the critical roles once attributed to them. One doesn’t always need DCI’s blessing, nor SMPTE standards, to succeed in the rollout of new technology. Looking back, the cinema market today looks a lot like the cinema market in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Market leaders drive new cinema technology, not standards.

If you think about it, the struggle that occurs when there is no market leader is in plain sight. SMPTE DCP is the poster child, and my second example. It was standardized in 2009, and with luck, a constrained version may actually rollout in 2017, 8 years later. For reasons too simple to admit, SMPTE DCP is not backwards compatible with Interop DCP, the draft version of the standard. Interop DCP enabled the rollout of digital cinema, and operates daily on over 160,000 screens worldwide. SMPTE DCP is the engineering attempt for a perfect world. The transition to SMPTE DCP represents a cost, not a savings. The only way proponents could generate value for SMPTE DCP was to hold back further development of Interop DCP (the documents for which to this day remain hidden on a passworded FTP site). Without further elaboration, this is not the model to copy when rolling out a new technology. However, that hasn’t stopped some from trying.

A successful market-oriented model for rollout was that of Dolby Atmos, my third example. Dolby took a lot of heat for not pursuing a standard upfront, and one can only imagine the internal kicking and screaming that led to the eventual opening up of the distribution format (no license required) in September 2016. But don’t let the bloody details detract from a successful strategy. Dolby’s technology rollout was successful precisely because it wasn’t constrained by the peer scrutiny of a standards effort. Further, Dolby provided financial support for its early rollout. It has been criticized for pouring its own money into its rollout, but pay attention: this is how the cinema game is played. Recall that studios also had to pour money into the digital transition to make it a success.

There is a standards effort for immersive sound now in progress, and it invokes a déjà vu experience: the strife for perfection while the market passes by. If it takes less than 8 years for the standard to replace Atmos, I will be the first to be impressed.

The lessons learned from the three examples above:

- Rollouts work when the economics work.

- Standards are optional.

- When considering a standard, go back to step 1.

One last point. The roles of DCI and SMPTE have matured. DCI is the owner of the DCI specification. It operates the DCI compliance program. DCI compliance establishes the baseline performance of cinema equipment, including, and most notably, security performance. DCI, on occasion, issues guidelines for new technology, but guidelines without teeth produce mixed results. SMPTE, as a standards body, is best thought of as a tool. Used properly, the tool can deliver great results. Used poorly, and you get what you get. If relying on either of these organizations to validate your new technology to the market, good luck with that. Even if such validation exists, remember to revisit step 1 above.

(Here are the slides from my presentation at the Beijing Film Festival: Next Generation Cinema: On the Way to HDR.)